A zoological history of the Americas: how animals, geography, and luck dictated the terms of 1492

I was sitting outside the Mirador de Sán Cristobal in Cusco reflecting on what I had just seen at Machu Picchu. A wonder of the world and a true testament to human ingenuity – but the timeframe surprised me. Constructed around 1450, this meant it was built a mere 42 years before Columbus set foot in San Salvador. I was looking at a stone-based society, one that would soon come into contact with steel and gunpowder.

In school, we learned that the Americas fell quickly due to technological differences and disease. But how did it come to be this way? What allowed Eurasia to discover steel and gunpowder while the Aztecs were still fighting with obsidian? Why was disease spread one-way – why didn’t Eurasians contract diseases from the natives? What caused 2 completely independently developing societies to drift the way they did – was it a property of the people, or their circumstances? Or, as I found, could you trace it back to the movement of animals?

Zoology starts with us

A zoological history of the world requires that we first take a look at ourselves. The humans that would start fighting each other in 1492 didn’t appear from scratch in the old and new worlds. Evolutionarily and statistically, that would be near-impossible. Both groups of people came from the same origin.

Hominids originated in Central Africa around 7 million years ago, though the earliest forms were more similar to modern chimpanzees than humans. The first member of the Homo genus (characterized by bipedalism and tool use, which start to look more like humans) emerged ~2.4 million years ago, and quickly spread across Eurafrasia, where they evolved into H. Sapiens (in Africa), H. Neanderthalensis (in Europe), and H. Denisova (in Eurasia). Today, only H. Sapiens (us) have survived (though we have Neanderthal & Denisovan DNA mixed into ours via past interbreeding).

The second key piece to this story is the Bering Strait or the Bering Land Bridge. This narrow strip of land connecting Siberia and Alaska is the only land bridge between Eurafrasia and the Americas, and has formed intermittently throughout history, primarily during ice ages when the sea levels drop. This means that typically the bridge has formed every 40k-100k years, with plenty of overlap with ancient hominids.

There’s 2 pieces of evidence combined, though, that all but confirm that human migration to the Americas only happened during the last formation, which lasted from ~35k years ago to ~15k years ago.

- H. Sapiens only successfully migrated from Africa into Eurasia ~70k years ago, meaning the land bridge from ~35k years ago to ~15k years ago was their first opportunity to cross into the Americas.

- No other Homo species have been found in the Americas – archaeological evidence only shows H. Sapiens.

So, we’ve established that humans crossed into the Americas between 35k and 15k years ago.

The “discovery of the new world” is often framed as 2 completely unrelated societies coming into contact with each other and happening to find humans on the other side. It’s even more interesting, to me, to view it as a never-repeatable case study – what happens if you take two populations of humans, who 15k years ago could have been brother & sister, and let them develop completely independently under different conditions?

That fated meeting in 1492 wasn’t a discovery. It was a reunion.

The setting of the table

Given the migration that resulted in the settling of the Americas, we know that the development of the next 15k years wasn’t a property of the people – they all came from the same place.

More likely, the outcome would be a result of other factors:

- The geography of the land

- The animals available to them

- The plants available to them

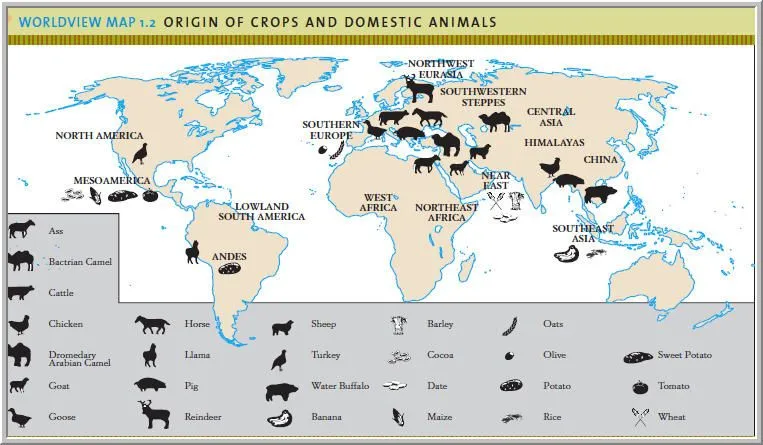

Next in this story is every other animal not named H. Sapien. Like humans, the same animal did not independently develop in multiple regions – this would be evolutionarily and statistically unlikely. Each animal has an origin, either in the Americas or Eurafrasia. Over millions of years, the land bridge has formed countless times, and megafauna migrated from one side to the other.

Some examples:

- Mammoths, Bison, Grey Wolves, Brown Bears, Cave Lions, Moose, and Antelope migrated from Eurasia to the Americas

- Horses, and Camels migrated from the Americas to Eurasia

It’s important to note that not every animal migrated – only the ones that could naturally exist in the Beringia climate already (cold!).

The humans who migrated into the Americas should have lived alongside many of the same animals as their Eurasian cousins, but their arrival in the Americas was very shortly followed by the megafauna extinction event, in which ~75% of North American megafauna & ~83% of South American megafauna went extinct as compared to ~35% of Eurasian megafauna.

While the global extinction was driven primarily by climate change as the ice age receded, there remains a significant difference between the impact on Eurasia vs the Americas.

Unfortunately, signs point primarily towards the presence of humans, in what’s called the Overkill Hypothesis. In Eurasia, animals had existed alongside hominids for millions of years, and had developed both avoidance behaviors and general resilience to human hunting. In comparison, American megafauna were caught completely unaware. When humans crossed the Bering Land Bridge during the last ice age, they quickly swept through the Americas, much like an invasive species of plants. It’s been described by scientists as a “blitzkrieg” – having no prior exposure to humans left the megafauna vulnerable, and they were quickly hunted to extinction for food and hides.

Unbeknownst to them, these early American settlers began sealing their own fate for the events of 1492 and beyond. In what would prove to have devastating consequences, the megafauna extinction in the Americas drove horses and camels to extinction. Even worse for the hand they were being dealt, horses and camels, which originated in the Americas, survived and continued to flourish in Eurasia.

This left all of the Americas without any suitable draft animals (animals that pull heavy loads) or transport animals (animals you can ride). And it left all but narrow regions of South America (alpacas) without any pack animals (animals that carry heavy loads).

In fact, the new world pretty much only had llamas, alpacas, and turkeys to work with. Every other domesticable animal was only available in Eurasia, including every animal we think of when it comes to farming: goats, pigs, cows, and chickens.

The spurs of innovation

In history, civilizations innovated in 4 ways:

- Out of necessity to better produce food

- Naturally as a by-product of time for curiosity and experimentation that is only possible once a food surplus has been achieved

- Out of necessity due to threatening rival powers

- Via trade & general relations with neighboring powers

A lack of draft animals

Agriculture began ~10,000 years ago in the old world (the Fertile Crescent) and ~8,000 years ago in the new world (Mesoamerica + Andes).

Both societies independently created digging sticks and hoes, the rudimentary tools used by human laborers for farming. The old and new world were equally motivated to improve the efficiency of farming, but the progressions largely diverged here due to the presence (or lack thereof) of domesticated animals [Innovation 1].

In the Americas, the ingenuity was still high despite the lack of draft animals. In the Andes, the farmers developed foot plows, which helped leverage body weight to till steep or hard soils. They also developed terraces, which were incredibly important for the farmability of the slopey land that the farmers had to deal with. In Mesoamerica, the Aztecs developed Chinampas, which were floating gardens on which more maize could be planted. Tenochtitlan, one of the most impressive cities in the history of the world, was built entirely on the shallow Lake Texcoco. These Chinampas were essential to add farming land to the city of 200k inhabitants (comparable to London & Paris in population).

Unfortunately, those innovations still led to a farming society that was labor-intensive and human-bound.

Eurasia, in contrast, had access to animals like the Ox, which they domesticated for farming use by 5000 BCE. Suddenly, plowing land in the old world became much more efficient than the new world could dream of. A much smaller % of the society was dedicated to food production, which left more time for urbanization and related advances [Innovation 2].

Urbanization leads to advantages in innovation. It gives rise to more inventors, scribes, smiths, specialists, guilds, and forums of communication in which ideas can flourish. This meant time for advanced mathematics, deeper administrative states, philosophy, and metallurgy. Urbanization also provides a feedback loop – it enables efficiencies at all levels of the civilization, which in turn creates even more room for specialization, and more discoveries.

This urbanization led to the discovery and widespread use of iron, the creation of gunpowder, and even the development of complex machines like the Printing Press by the time the new world was discovered in 1492.

A lack of transport animals, and a North-South geography

Generally, civilizations in the Americas had a much smaller radius of other civilizations they could interact with, due to the lack of horses. A society that can only travel on foot can only extend their sphere of influence so far.

This meant fewer societies to compete with militaristically [Innovation 3] and fewer societies to trade and learn from [Innovation 4].

That’s not to say that societies in the Americas weren’t militaristic – that’s definitely not true, they were highly militaristic. But the density of civilizations with which any one civilization could interact was also heavily constrained by geography.

Eurasia is an East-West axis. By comparison, the Americas (and Africa for that matter) are on a North-South axis.

On an East-West axis, climates are generally similar. This means that it’s easy for people to move between civilizations, for successful agriculture to move from one civilization to another, and for there to generally be more interconnected civilizations. This increases both (a) the # of civilizations you can collaborate with and (b) the # of civilizations you may go to war with.

By contrast, a North-South axis poses many challenges to interconnectedness. First, there’s isolated ecosystems. A crop that succeeds in one region may not succeed just a few hundred miles North or South. Maize famously took millennia to adapt to colder climates such that it would be farmable in North America or the Andes. Animals also don’t diffuse on a North-South axis– the alpaca remained local to the Andes, unable to successfully adapt to flatter regions.

Lastly, successful civilizations end up with huge inhospitable landscapes between them. The Andean and Mesoamerican civilizations had very little crossover, because the jungles of Central America were largely inhospitable. Especially with a lack of horses, traversing unfriendly terrain becomes a challenge. Any contact (and there is some evidence there was some, particularly the similarity in metallurgy) would likely have been via seafaring.

Eurasia had the advantages of both being wide in its hospitable land and traversable via the existence of transport animals like horses. The distances were great enough that civilizations could develop independently, yet still have contact and conflict. That bred both innovation through competition and collaboration, something the Americas weren’t able to benefit from.

But what about disease?

A lack of transport animals, draft animals, and a North-South geography explains the difference in innovation by the time the worlds met in 1492.

But what about disease? Why did only those in the Americas get affected? Why didn’t Europeans get sick with American diseases? A staggering 90% of Native Americans have been cited as succumbing to disease – how could this have happened?

The answer goes back to 2 things we’ve discussed: urbanization and domesticated animals. Simply put, Eurasians formed many urban centers and lived in close proximity with many animals. Those urban centers were often dirty and with poor hygiene, which served as a breeding ground and subsequent playground for plagues.

Plagues like tuberculosis and smallpox weren’t bred or meant to kill humans. These are diseases that came from domesticated animals, for whom these aren’t a big deal. Tuberculosis for a cow is like a common cold for us.

Germs jumping species is extremely rare – but the old world had millennia to play this deadly lottery. Humans in the old world lived in close quarters with animals since at least 5000 BCE, which gave more than enough time for some of these fluke diseases to take hold.

Given that alpacas were pretty much the only domesticated animal in the Western Hemisphere, there simply wasn’t much opportunity for plagues to develop. And so, fortunately for the Europeans, there was no America Flu to take back to the old world.

The cards that were dealt

Sometimes, you sit down at a poker table, and you draw a 2-7.

The game of civilization between the new and old worlds could always have shook out this way. The animal genetic lottery could have favored the Americas, Eurafrasia, or have been more equitable. As it turned out, some factors were just stacked against the Americas:

- More domesticable animals evolved in Eurafrasia than in the Americas.

- Humans migrated into the Americas, killing off potential domesticable candidates before they were evolutionary prepared to deal with humans.

- The Americas had a North-South axis rather than an East-West axis like Eurasia, which hindered movement, collaboration, and competition in the Americas.

The meeting in 1492 was set in motion long before that date.