Map-Based Strategy & Product Vision: How EU4 made me a better Product Manager

For years, my favorite game has been Europa Universalis IV. Most of you probably haven't heard of it. It's a long, grueling grand strategy game in which you manage a country from 1444 to 1821. There is no "goal"; you can choose one yourself on every run. Each run takes ~35 hours. I have hundreds of hours in the game, and have played as all sorts of nations – big, small, rich, poor, technologically advantaged, archaic, surrounded, isolated, warlike, peaceful, and more.

The first time I sat down to chart a product vision, I did it wrong. I only thought about what my customers & prospects were telling me. "We want this feature!" "We want that feature!" I understood that we wanted to be better than our competitors (obviously), but I was stuck at a feature comparison level. I wanted to reach parity where we didn't have it, and exceed their capabilities where we could.

This approach wasn't completely wrong– it's good to swim in customer feedback, and good to think about the features competitors have. But product strategy involves a lot more. In November, I took Shreyas Doshi's Improving Your Product Sense class. I'm not usually a big believer in courses– the price tags are large, and the LinkedIn certifications seem decorative. This course, though, legitimately changed my view on product management and business strategy, I can't recommend it enough. Specifically, we spent many hours discussing Strategic Thinking, Positioning, Segmentation, and Differentiation, which transformed the way I started to think about products.

When I came back from the course and started to implement my learnings at work, I felt a familiar sensation. I really started to think about my product's place in the world. I took time to feel out who my neighbors were. What were they focusing on? Which ones might be a threat to my goals? I was also looking beyond my neighbors. What are my ambitions overall? What should be my path to get there?

In essence, I moved from thinking about competing on features to thinking about my product's place in the world, what we wanted that place to be, and how to get there. As I worked through the process, the parallels became clear to me. I was playing grand strategy on a real-life, grand scale. The right choices would lead my product to grow, capture more market share, and succeed in comparison to my competitors. The wrong choices could lead to the extinction of the product itself.

Since then, that frame of mind has influenced my product thinking not just at work, but with personal projects, observing developments in the AI space, and analyzing M&A activity. It has honestly made all those things more fun – I feel like I can clearly see what companies and individuals are trying to do, how they're positioning, and what they hope to get out of it.

Small player strategy, big player strategy, M&A, upwards momentum, downwards spirals. All of these manifest in both the business world & EU4. Let's get into it.

Small Players: Focus fuels Survival

When you load into a new game as Brittany, or Savoy, or Tlemcen, or Malwa, or any other of the hundreds of smaller nations in EU4, you have an immediate problem: your most powerful neighbor. Just like history has shown, all the diplomacy in a region revolves around its largest power, and the only way to truly achieve safety and stability is to become that power. Becoming that power is not easy! It's not just you and your will to attain that goal. The reigning power in the region is doing everything they can to maintain their dominance. And every other country vying for position is looking to better their situation too.

Take Byzantium for example. When I load into the game as the Byzantines, I'm immediately met with a precarious situation – I'm directly in the path of the (extremely powerful) Ottoman Empire's expansion.

Operating without focus, therefore, is destined for failure. I can't just play with a "generic" strategy, going through the motions, maybe making a random alliance or two and investing in admin/diplomatic/military power equally. I'd be overrun.

Focus comes from a strong vision, just like the startup world. If I waffle with indecision and uncertainty, I have virtually no chance of surviving the coming decades. For the Byzantines specifically, the strongest vision is military focus and strong alliances – I need to immediately set myself up to survive the war with the Ottomans.

Internally, I need to make sure my house is in order and the whole country is rowing in the same direction. I immediately need to invest heavily in my military. High level military advisors will help me advance my military tech level quickly, which is essential to match the ottomans. I'm going to need to recruit as much infantry as possible, hire mercenaries when the war starts (so I'm going to need the funds for it), and make sure I develop 1 or 2 extremely strong generals. There's even some underhanded tactics that I might have to put in play – I know my successor is more promising than my current king; as such, I might have to scheme my king into a generalship so he "accidentally" passes away, making way for my stronger successor.

Externally, I'm going to need strong alliances (aka partners). I have options here – I could ally with a few small nations (Albania, Wallachia, Bosnia, Karaman, etc), or focus on securing an alliance with one or two large nations (Poland, Hungary, Mamluks). Whichever way I go, I again need focus. I only have a certain number of diplomats and diplomatic points I can pour into it. Large nations will take a lot of work to win over, but could be fruitful. Smaller nations are easier, but less helpful in wars, so I'm going to need a lot of them. What I can't do is half-ass either one. I need to pick a strategy and commit to it.

The Byzantine situation is one of many, but the theme is true of every small nation: you need a focused strategy and align both micro & macro decisions around that strategy. That focus has no single right answer – it could be overwhelmingly owning a trade node, or becoming the strongest naval power, or cutting off a large power from a given resource/technology. Again, what matters is committing.

And the same, I'd assert, is true for any startup. Choosing a specific positioning in the market and segmentation to go after is essential to focusing on the right features and the right differentiation for the right customers. Without it, you're just building into the void.

With that focus, you then start aligning all internal and external actions to that goal. Internally, you have so many levers to pull – OKRs, KPIs, internal processes, personnel allotment, and more – just like in EU4, where you can pull on government type, advisor hires, religious focus, national ideas, and a million other mechanics. It's up to your leaders to pull everyone in the same direction, and it's necessary for a victory.

Externally, you're going to look at the best way to reach customers. You may develop partnerships and co-sells (alliances) that benefit your users to give them a more complete solution while going up against bigger players. You may cozy up with other startups in the hopes of lifting all boats at the same time. You may even throw some doubt on your competitors (covert actions) that grow your influence in the world and diminish your competition.

My favorite podcast of late has been Acquired, by Ben Gilbert and David Rosenthal (I know, I'm late to the game). A recent episode on Rolex provided a great example of this focus. When the Quartz crisis hit the Swiss watch industry in the 1970s, most Swiss watchmakers panicked. There was a quick pivot into quartz-based watchmaking, and tons of consolidation across major watch houses. Rolex, however, stayed steadfast. While they did of course experiment with quartz watches, they refrained from pivoting the whole company into its pursuit. Rolex instead stayed laser-focused, doubling down on craftsmanship, reliability, and timelessness of its watches. The reward: it grew into a new, more upscale market borne out of excellence, rather than chasing the downward price spiral of "everyday watches". That focus wasn't just on the product side either; the whole company swam together. The marketing team put out clever campaigns associating Rolex as an aspirational symbol:

This coordinated, both internal and external focus on becoming a luxury, craftsmanship-based brand yielded undeniable results. And had they swum around aimlessly, Rolex would likely not be the giant brand that it is today.

The goal of a small nation is to become that large, dominating presence in that region. Focus ensures survival – from there M&A activity and upward spirals can help drive the rest. We'll get into those in later sections.

Large Players: Managing an Empire

Your concerns are a bit different when you kick off a game from the advantageous positions that nations like Russia, France, and Austria find themselves in. Your equal-footing competitors still exist, but there's often a gap (literally, geographically) between where you stand and where they stand. In those gaps, hundreds of smaller nations are carving their place out in the world, all of them available to you as possible bets to make. While your stability militarily is often a given, pressures mount internally and expansion can jump-start instability. It takes restraint and careful directional calls to keep the empire afloat and expand it without making catastrophic mistakes.

Take France, the quintessential example of a large nation to start with.

The start is easy – I'm at the technological heart of Europe, I have a large and well trained army, great generals, and everyone would love to be my ally. I have a litany of options for expansion: English Normandy to the North, the Low Countries to the East, towards Italy (Savoy/Provence/Genoa), and Iberia to the South.

The real dangers to my nation come in the form of competitive actions by other large players, internal instability, and the dangers of overextension.

My most straightforward task is to monitor what England, Aragon, Castille, and Burgundy are up to, just like as Meta I would always be monitoring what Apple, Google, and Microsoft are up to.

Next, Meta definitely won't be staying stagnant. It's going to look to expand into new industries and increase its reach. VR, multiverse, chat, Gen AI and more. Sometimes, the exploration is more green-field like VR & the multiverse. I'd liken this to expanding in the direction of smaller players in EU4, and aiming to take over a nascent industry. Other times, the exploration is directly up against other big players, such as Threads being launched to compete with X. Whether it's starting a war with little Brittany or powerful England, everyone is looking to expand.

The danger, then, comes in the form of expanding too quickly or too aggressively. If I launch wars with England, Aragon, and Burgundy at the same time, of course I'm going to lose, as I'll be spread too thin. Even if I space them out, and don't give time for my nation to recover, I'll suffer from war exhaustion, very similar to burnout that employees feel. And even if I do win, I'll likely struggle with overextension and the issues that come with trying to maintain an advantage on multiple fronts at the same time. Meta has thousands of companies in its sphere that it could theoretically replace and run over. They have hundreds or thousands of smart people too – but if they spread them too thin and try to accomplish everything, the organization will suffer.

Even with vast resources, major powers face real limits on how much they can effectively manage at once. And that's what really gives space to startups. It's not that Meta & Google couldn't do what you're building. It's just not in their best interest to do so.

M&A as Strategy: Vassalization & Annexation

One looming threat and opportunity, no matter the size of your company/country, is M&A activity.

As a smaller nation, while you may be focused on dealing with the largest power in the region, you have to keep an eye on your close competitors. Companies & countries of similar size can suddenly become a threat due to M&A activity/conquest/vassalization.

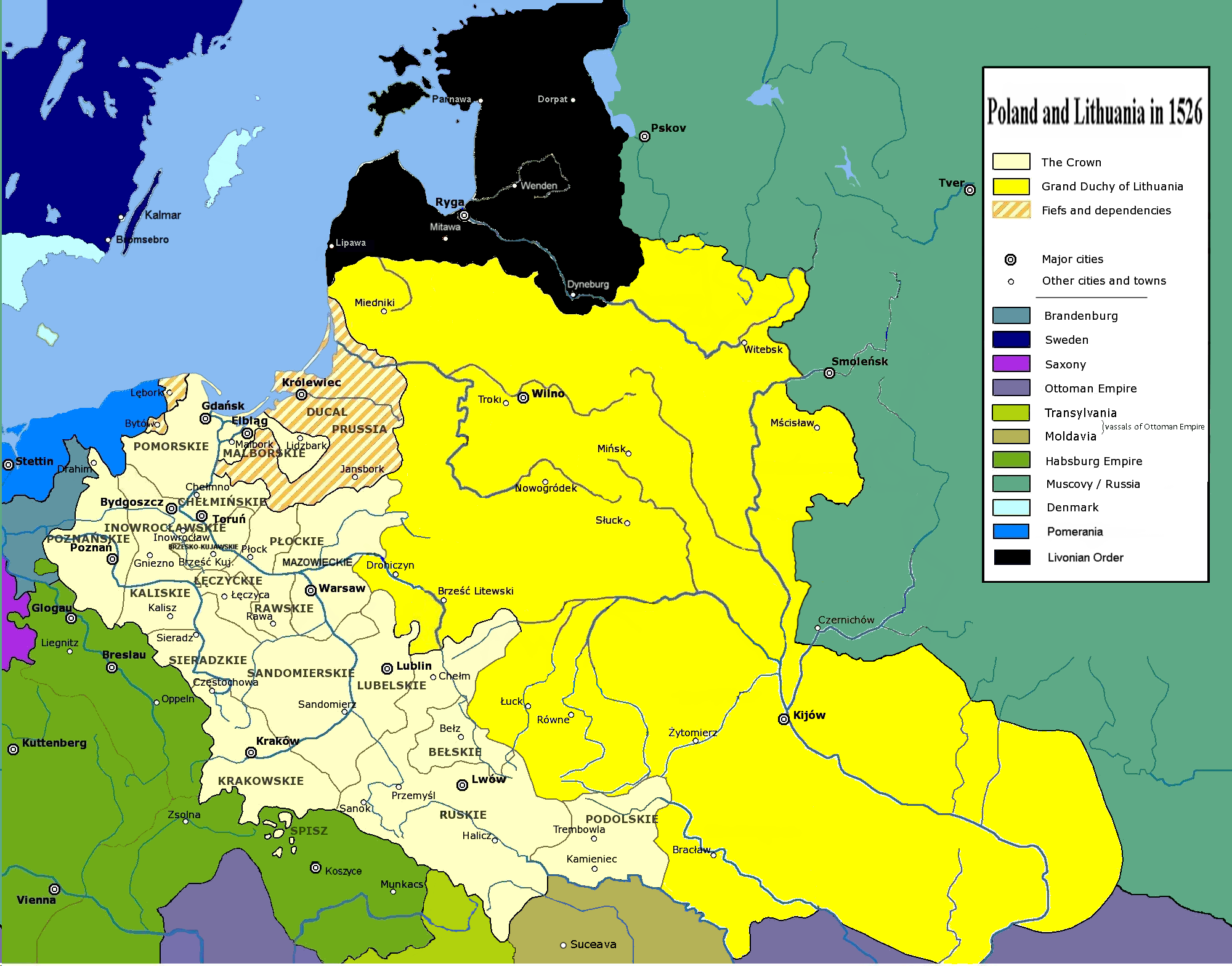

Starting as the Teutonic Order, for example, can feel almost comfortable.

Some threats on either side, for sure, but nothing that will get you overrun instantly. You have a likely ally or two in Brandenburg and Bohemia, while Poland and Lithuania loom large but have similar military powers that you may assume will conflict with each other.

This turns quickly though, if/when Poland establishes a Personal Union over Lithuania, as they often do (and historically did). Suddenly, you have a monster on your doorstep, and the game quickly turns into a bid for survival.

Other entities merging is of course a threat, but there's also an opportunity in dissolutions. Often as a result of instability or lost wars, countries will break apart and release smaller states. It's not just the lessened size of the original entity that represents the opportunity – maybe that spun out business is an opportunity for a new partnership, or even something you yourself can conquer and displace.

M&A for your own company is important to consider as well. As a large company, you're often faced with a choice– should I build in this direction I'm trying to expand (conquest), or should I just acquire an existing solution with their team (vassalization)? Both have their pros and cons– conquest allows more direct control, but more growing pains, while vassalization leads to lessened control but a largely still-happy population.

Even the opposite, a spin-out of a company/country can be useful under certain situations where a certain sector is causing a lack of focus in the rest of the organization.

And lastly, when things get dire, it's often better to allow your own company to be acquired/vassalized than to slowly die out over time. This often comes with some promises of autonomy and a better outcome for your people – founders and rulers often battle the urge to fight to the bitter end, negotiate favorable terms of surrender, and take an exit instead.

Internal Stability: Succession, Culture, and Integration

Mergers, acquisitions, change in guard, expansion – all of these things can put stress on a company's culture and stability.

Each expansion comes with its own cultural identities, preferences, and customs. In EU4, these are represented by cultural and religious turmoil – conquer a province of a different culture, and the citizens will resist enough that they'll even openly rebel if not properly dealt with. Religion especially can tear a country apart, and too many rebellions can lead to the entire nation collapsing.

When M&A occurs, or in general when a company expands into new segments, these same dynamics occur at companies. Even absent of M&A, certain departments of companies will develop their own cultures that differ from every other department. If left unchecked, these can start to vary widely over time. Acquired companies will sometimes differ so much in culture that the organization will "reject the organ" and the acquisition will outright fail. Just like EU4, the organization has a choice– do they try to convert dissidents to the same culture as the rest of the company, or do they loosen their policies to allow for different cultures. Converting has a long-term benefit of homogeneity, but the short-term issue of even stronger unrest.

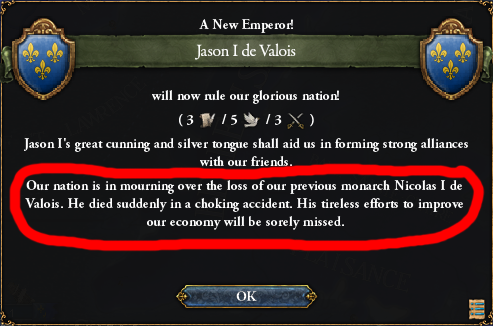

Changes in succession have a similar issue. In EU4, any time the ruler is displaced, the entire country takes a stability hit. Even if the new ruler is a huge improvement on the previous one, any change of guard will have a stability impact on the country. The same is true for founders, execs, and other powerful figures leaving the company you're at– no matter how well-managed the transition, unrest grows when turnover occurs.

The Spiral Dynamics

Downward Spirals

When it rains, it pours. And that's true for both your country in EU4 and your business in real life.

Take a lost war in EU4. My people will take a huge hit on happiness from the war exhaustion and the lost prestige from having lost the war. Army morale and discipline will take a hit for similar reasons. My military manpower will be near-zero, and I'll struggle to field a competent military in the near future. Economically, my country will be left hurting. I'll likely have outstanding debts I need to pay back, and my income will be lower than it used to be due to the lost territories and their tax/trade incomes. Diplomatically, my reduced size and prestige will make it harder to maintain powerful relationships. The quality of my allies going forward will probably take a hit.

Now let's look at your business, which lets say lost to a competitor in a given segment. The morale of the company will take a huge hit. People will both be ashamed from losing the battle and exhausted/burnt out from all the effort they put into a failed initiative. Many will leave. Recruitment will be difficult – it's very hard to recruit top talent when your most recent product push failed and there isn't a strong growth story. You'll have burnt a good chunk of your runway/budget on the effort and will struggle to muster up more – raising more from investors will be tougher, same with asking execs for more budget. Lastly, partners will have less of a reason to work with and promote you. Loyalties change fast, and those partners won't have much of a reason to not go with the competitor you lost the segment to.

With all the resource, manpower, economic, and diplomatic hits you take, the next war will be even tougher. Therein lies the compounding path to failure.

For a big company, a loss like this may not be so brutal. The size implicitly gives you a buffer to take losses on the chin, regroup, and recover. For a small company, a loss like this can be a nail-in-the-coffin for your business. A significant loss in EU4 can put you in rebuild mode for 5-10 years, praying that no other sharks circling your nation choose that moment to strike. If they do, it's often curtains. If they don't, you still likely end up 20-25 years behind on your strategy compared to where you hoped to be.

The spiral can be broken, though, only with intense focus. If I lose my war with Austria as Bohemia, for example, it can be easy for me to quickly let the situation spiral out of control.

Other HRE nations could pounce, I could lose my position as an elector, and even Poland could pounce from outside the HRE assuming that Austria would be uninterested in defending me. On the other hand, I know a way I could claw my way back– by focusing solely on the diplomatic game, I could attempt to win back emperorship of the HRE, and begin consolidating power again that way. If that's my strategy, I need to go all-in on it. I need to prioritize diplomatic ideas, overspend on diplomatic advisors, go over my relationship limit and take the associated hits – anything to achieve my goal of claiming that emperorship and re-establishing my position.

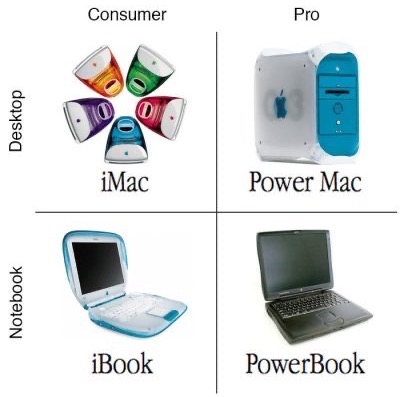

In 1997, Apple was deep in crisis. Steve Jobs had been ousted in 1985, leading to a series of problematic decisions made by new management. Apple had launched a bewildering array of models: Performa, Quadra, Centris, LC lines. These had little clear differentiation and confused consumers. They lost significant market share to Microsoft, to the point where there were rumors of acquisition by Sun Microsystems or IBM. In early 1997, Apple posted their worst financial result ever – a $700 million loss in 1 quarter. Morale was low, prestige was in the gutter. Media outlets like Newsweek were calling it A Death Spiral, and the end seemed near.

When Steve Jobs returned, his focus was incredibly intense. He cut the entire product line into 4 products: two desktops (consumer and pro) and two portables (consumer and pro). He killed off many R&D projects and many products, instead focusing on a single, beautifully designed product in each of those four categories. He focused the brand around the beautiful design, and relaunched new products as soon as 1998 that matched that marketing. It was an immediate success: the 1998 iMac sold 800,000 units in the first year and became the fastest-selling PC in history.

If Steve Jobs had returned and tried to save every product at once, he would've failed. In essence, that's what two of his predecessors had tried to do. They focused on cost-cutting rather than key strategic issues, and added even more product vectors like licensed Mac OS rather than focusing on a single strategy. It's clear that Steve Jobs succeeded because of both his vision to determine a focus and his willingness to commit to it.

Downward spirals are absolutely lethal. For Apple, it almost was. And while the compounding effects are very real, intense focus can pull your company out and into brighter days ahead.

Upward Spirals

The good news is that upward spirals exist too!

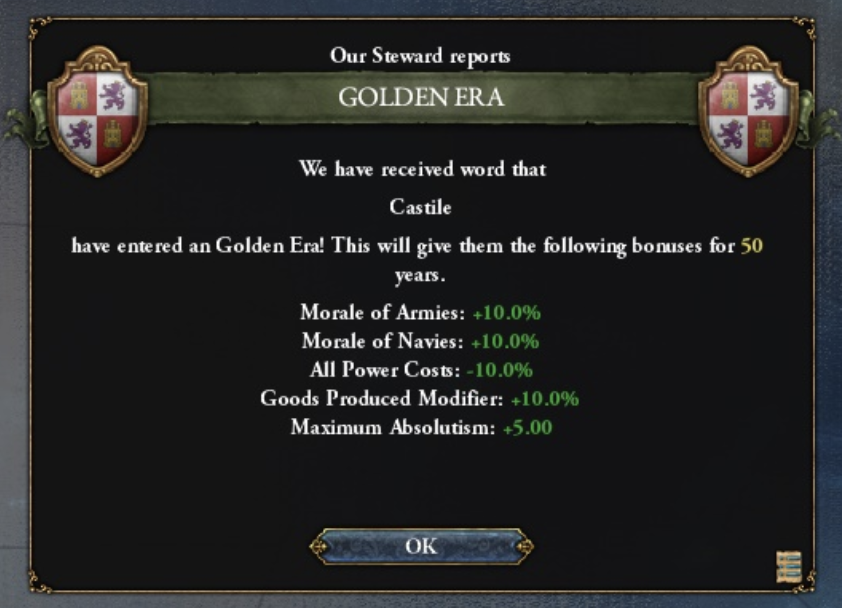

Winning a war has some great benefits. People in my country are happy to be part of a winning country. Economically, I've added tax income and trade power by adding territory. With a stable income and the reduced threat from the neighbor I just defeated, it'll be easier to invest more in my long-term future, and I can invest in those initiatives from a place of stability. Morale, discipline, and professionalism of my army will be sky high. It'll be easier to recruit new soldiers. Diplomatically, I've increased my standing on the world stage. I may find new, more powerful allies, and gain more concessions from the neighbors I already have. Even my visibility has increased – far away lands will note that I won a meaningful war, even if they don't act on it right away.

A successful product initiative yields great results too. Company morale will be great. The added revenue gives me a buffer from which I can continue to make long-term bets, and take the time to do so carefully. Bringing in more budget or funding rounds is easier too, now that I have some success to show as proof. Recruiting new, talented engineers will be easier. And within the business world and ecosystem, competitors and observers alike will notice. More powerful partners will want to work with me. My interviews on CNBC, my LinkedIn posts showing proof of success – all of these lead to an increase in prestige that makes everything to follow easier.

The dynamics of upwards spirals are rather self-explanatory, so I won't dive too far into examples, but they're everywhere to be found. In game, securing trade routes as Venice quickly leads to exponential economic growth, leading to exponential naval growth, leading back to more exponential economic growth. In business, key victories take many forms. Sometimes it leads to another funding round, signaling to the world that you're a serious contender, giving both partners and customers greater confidence in your work. Sometimes it leads to a favorable Gartner report, which brings in more customers, which brings more feedback, which helps you continue to build the right product.

Positive flywheels are everywhere, and the important thing is to capture that momentum and swim upstream with it. Continue to make long-term bets. Use economic tailwinds from the previous initiative to fuel the next one. Keep recruiting talent while your position allows it. Recognizing when you're in this loop and continuing to make effective product bets is how you stay in it as long as humanly possible.

Some Reflection

While writing this blog, I had a perhaps obvious takeaway start to form: while my frame of reference here is a video game in EU4, the real lessons stem from history – civilizations have had to manage these same considerations for millenia. Maybe, to some extent, that's what capitalism has given us. A playground on which we get to play civilizational-level games in a new arena.

And really, I think that's why I like it so much. This lens on product management has made me think of my work not so much as a job, but as a true game of intellect against the other players in the world. There's a myriad of factors that play into success or failure other than my own thinking, of course, but the truth is that every product owner (whether they're a PM by title or not) is playing the game. And the quality of your thinking does greatly affect the outcome.

So, yeah, I like the game.